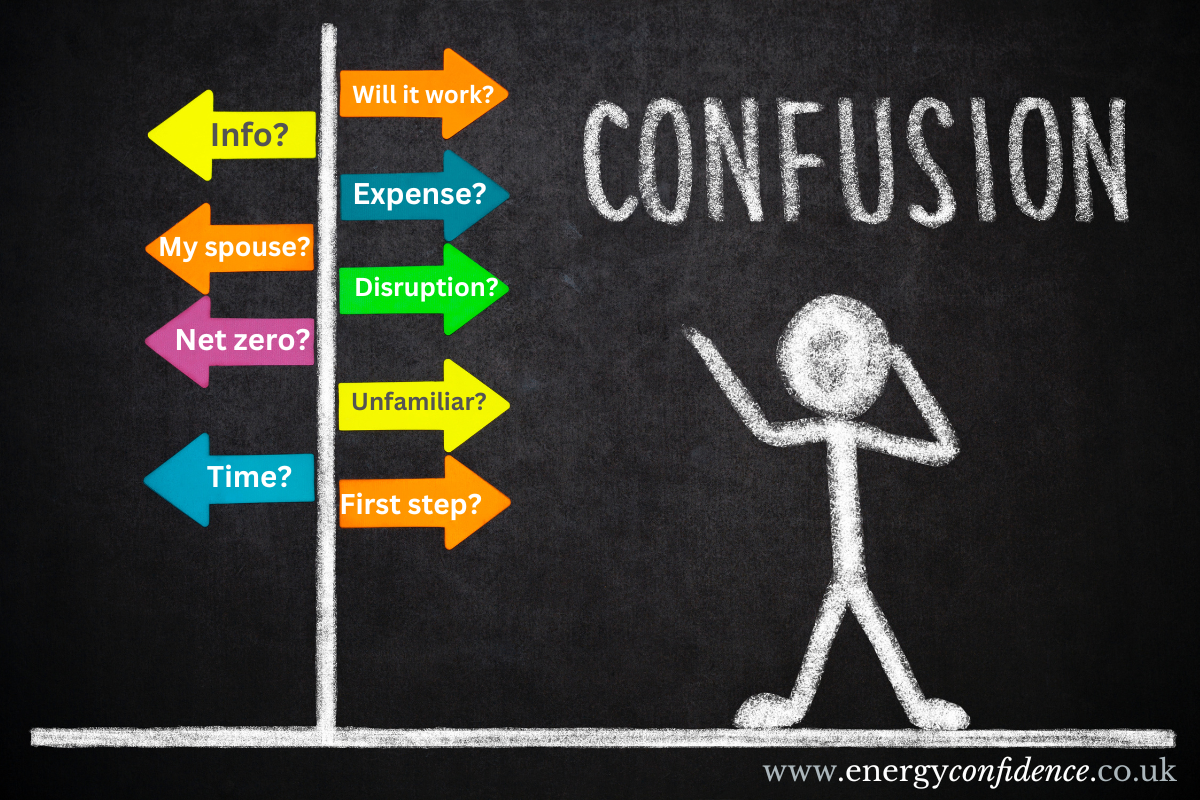

What are the most common types of objection to energy saving measures?

And how can we deal with them in a way that centres the needs of the householder?

- I need more information.

Some examples of this type of objection are:

- I don’t know if a heat pump would work for me, and I need more information on how it would heat my home on a cold night, and still be affordable. It’s not difficult to understand why. Most people have not seen a heat pump working in a home. They are more likely to have read an article in a hostile newspaper than to have seen a heat pump. You need to listen to their objection and find out what their fears are. Once you know their fears you can tackle them.

- I need more information on this ventilation system because I am concerned that it will be expensive to run. Most homes in the UK have inadequate ventilation; you need to be able to show to the householder the benefits of proper ventilation and the role of ventilation in reducing moisture-related risks. Most householders have limited understanding of this. Once you have done this you need to be able to show them how improvements in the efficiency of ventilation system mean for their actual running costs – since there is an urban myth that they use a lot of electricity.

- I don’t know where to start, or what to do first. We need to invest time in showing householders what the energy saving hierarchy means in their home, and in what order we should do things. Transactional or measures-based approaches fail to do this, and cause confusion and suspicion. Householders often know more about their home than we do, and we should use this knowledge, and work with it not against it.

- I need to know if the energy saving measure is guaranteed. Big energy saving measures such as insulation and heating systems will have a guarantee but it’s not always obvious to householders how they activate the guarantee if anything goes wrong. It is an essential, but often overlooked, part of the handover of energy saving measures to ensure they are given adequate information about guarantees.

- What aftercare do I get? Many energy saving measures are handed over without any aftercare. Examples of aftercare that should be given or shown include: how to fix things to walls that have been insulated; how to use heating controls; what is the expected impact of solar panels that have been installed. Yet this aftercare is often neglected. I get many enquiries from householders about this, where they are in the dark about how things work. This includes people who have moved into a house with energy saving measures, where the landlord/letting agent/estate agent has no idea how they work. There needs to be proper aftercare, including to people who lack fluency in written or spoken English, and retrofit passports for houses that are resold or relet.

2. Will this work in my home?

People won’t buy what they haven’t seen. Most people have now seen solar panels. Very few people have seen a heat pump in a home in the UK. We need to be able to exemplify homes that have them – schemes like Birmingham Green Doors and Superhomes do this.

3. I need to speak to my partner first

Within a household, there is often the perception of conflicting views. It is commonly assumed that goals such as saving the planet, saving money, and keeping warm are in conflict with each other. This often takes the form of “my spouse is an environmentalist who is motivated by saving the planet, whereas I am mainly concerned with saving money and keeping warm”. In reality these goals are not mutually exclusive and it is possible to persuade people that you can save the planet, save money, make the home more comfortable, and improve the value of a home. Key to this is a whole-house energy strategy. Starting with a shopping list of energy saving measures makes it harder to synchronise goals that are seem to be in opposition to each other.

4. It’s too expensive

Some energy saving measures are expensive. Some installers of measures such as solar have given these measures a bad reputation by mis-selling systems that are over-priced because most people don’t have a benchmark against which they can compare prices. A good energy saving strategy for a home will include a mixture of measures, including low-cost and no-cost measures. A good advisor will highlight no-cost and low-cost measures such as heating control improvements, to win the confidence of the householder so they have a better understanding of a whole-house approach and don’t feel under pressure to spend money on things they don’t need.

Some householders believe that they need to fit every single energy saving technology available to make a difference. This is not always the case. A long-term energy saving plan will include measures that can be implemented now; measures that can be implemented in the next five years, and measures that can be implemented in the longer term. This means that the householder doesn’t necessarily need to spend all of their money all at once. Some householders (and businesses and public bodies) have a perception that they need to reach “net zero” by a certain date (e.g. 2030). I do not wish to discourage people from aiming for net zero. But there is always a pathway that a home needs to follow to get close to net zero in the future. An abstract target at a date in the future can be paralysing. Energy saving is all about goal setting, with interim milestones as well as long-term goals. It’s the interim milestones that are empowering because they give people something achievable to aim for. A good energy saving strategy for a house will identify the key measures that will make the biggest progress in approaching net zero. It will also tell the householder what they shouldn’t do. For example, “you need a PV system of 4 kW, not 8 kW”. “You don’t have enough land for a ground source heat pump, but a properly designed heat pump will reduce your carbon emissions from heating by 80% (typically).”

5. I am going to do something else instead

Sometimes you will advise a householder to implement energy saving measures, and highlight the priority measures that will make the most difference; but instead they implement something that was much lower down your list of recommendations, and which will make less difference. There are valid reasons why they might feel comfortable doing this. This can be frustrating but use it as an opportunity to remind them of the long-term energy saving plan, and plant the seed in their mind that they might implement some of the other measures in future. Energy saving schemes often have a short-term transactional approach, based on meeting a target (e.g. install 10,000 heat pumps in Anytown by 2025) that is meaningless to most people. Householders don’t think that way. There will be other opportunities for deeper energy saving interventions in that person’s life at some point in the future. Make sure that they know that they can come back to you when that happens. Let them know that you are interested in their future.

6. I have not heard of the installer

This is understandable. There is a boom-bust cycle in energy saving due to the short-term initiatives of successive governments. This leads to churn in the energy efficiency industry and makes it difficult for installers to establish a reputation. I advise householders what to look out for in terms of accreditations, trading history, customer reviews; but this isn’t always enough. What helps a householder to have confidence in an installer is when I advise the householder what to expect. Some energy saving measures (glazing, loft insulation, kitchen appliances, lighting) are relatively easy for regular householders to understand. Some of the measures we need to achieve deep cuts in emissions (external wall insulation; heat pumps) are more complicated than householders are prepared for, and involve unfamiliar concepts and language. It’s important to prepare householders for what will happen when someone comes to survey for these measures. That gives the householder a benchmark against which to decide whether this installer is right for them or not.

7. I don’t have time for this; it’s disruptive

Undertaking significant energy saving improvements to a home can be time-consuming. The time spent in gathering information and making decisions can be stressful. A good advisor will provide a hand-holding service to householders. This helps to create a psychologically safe space in which people can make major decisions about their home. This means that they will feel that the time they spend is time well spent, rather than time wasted.

8. So what does “retrofit” actually mean?

I have seen energy saving schemes that are good at the initial engagement of householders, and then at the end of what seems like a successful conversation, the householder says, “so what does retrofit actually mean?” The word retrofit is of course jargon, it’s an unfamiliar term, that isn’t salient to most people’s experience. I have tried to avoid it in this article. We should think very carefully about the language we use.

Do you really need to use the word “retrofit”? Is there another word you can use instead?

It’s important to note that many of these objections apply whether the household is paying for the measures or not. With the exception of the cost-based objections, all of them can and do appear whether the energy saving measures are self-funded or grant-funded. That’s because they are rooted in genuine fear of what might go wrong; these objections should not be poo-pooed, but welcomed. Those involved in advising householders on energy saving measures need to acquire sales skills that will help them deal with genuine objections in a way that centres the householder’s needs, rather than centring the scheme manager’s needs.